A Filipino heart in Canada: Reflecting on the cultural disconnect linked to colonisation, shame, racism

Posted July 24, 2025 12:31 pm.

Last Updated July 24, 2025 1:41 pm.

This is the second installment of a three-part CityNews Connect series exploring Filipino identity in Canada.

The series follows CityNews reporter Joanne Roberts’ journey to reconnect with her Filipino roots and find a piece of her identity that’s been missing for a long time.

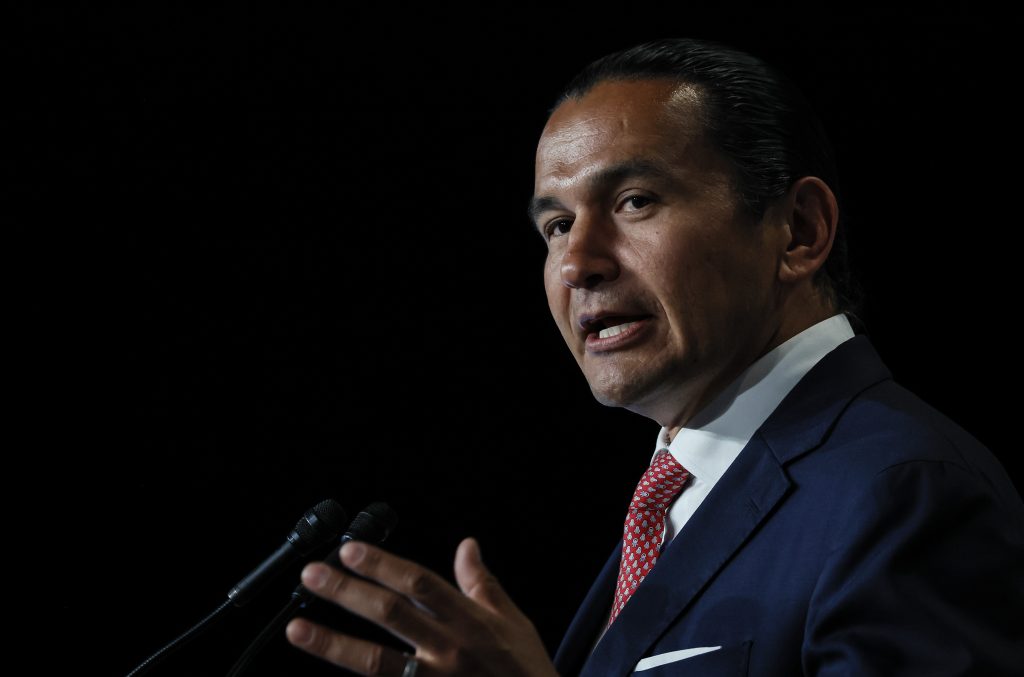

That search began with historian Jon Malek in Winnipeg’s garment district, and now shifts towards sexologist Dr. Reece Malone.

Joanne: So you and I have known of each other and known each other for a little while, but we never actually connected. This is the first time I’ve seen you face to face, even though I’ve wanted to work with you for a very, very long time. I think it’s just the perfect way for us to have our first real conversation, I would say.

Can you tell me what you do for work?

Reece: I am a sexologist, and as a sexologist, I do actually multiple things. I am a community-based researcher. I’m also a clinical therapist that focuses on human sexuality issues or sex therapy. I’m not sure if I told you. I also work at Ka Ni Kanichihk (Inc). So they brought me on as their consultant to the kookums and the Elders.

So I’m working very, very closely because our roots are….

Joanne: So similar.

Reece: Yeah, there’s similarities. I’m also an instructor and teacher at an institute in the United States, and I’m also an editor. So, curating a number of writers to uplift their voices and contribute to our culture and society. So I do a variety of things that bring me a lot of joy and abundance in my life.

Joanne: Part of this special that I’m shooting, it’s something that I don’t really talk very much about. So, you know, people know me as Joanne Roberts. That was the surname that I took when I got married. Before that, my maiden name was Fabro. But for me, just being a first generation Canadian, I never really felt connected to either of those names.

I knew growing up that I wanted to change my name and that’s, you know, because I had a very difficult family life. And I think I just wanted to disassociate from that. And I noticed that, you know, Malone is not necessarily like a Filipino or Spanish name either. And I was wondering what your history was for that.

Reece: My mom’s maiden name and my father’s last name also have deep meaning as well. My name is my partner’s or my spouse’s name that I took, and I did it for multiple reasons.

The decision was bittersweet for me to change my name. As someone who is in a field that is very vulnerable, people are uncertain to see someone, to talk about one of the more intimate parts of their life. I wanted them to feel safe, meaning approachable. I want them to be able to approach me and not have any psychological barriers why they may choose or not choose me.

I have to be mindful of like my skin colour, being Filipino, having a very Filipino name. Can people who see me pronounce my name? Is that going to be a barrier as well? And I also knew who my audience was. I mean, you need some kind of financial privilege to see a therapist. And so I knew who who was going to see me and who wasn’t going to see me, even though I have avenues and venues for those who may not be able to afford therapy. But the bittersweet part of it is the agency, and at the same time, really thinking about… is my internalised racism coming forward and what does that mean for me to not keep my name?

And so I had to really reconcile the legacies that my family held with their own internalised racism that was accidentally passed on to me, which was not their intention. It’s now my responsibility by naming it, to be very intentional with my choices when it comes to my identity, so that I’m in relationship with my history and in relationship with who am who I am as an authentic being.

Joanne: For people that don’t know what internalised racism is, can you give us just a bit of a quick note as to what you mean when you say that?

Reece: Internalised racism as a concept in which we may be exposed to other forms of discrimination that may be race-based. Whether it be because of the colour of our skin or ethnicity and culture. And we often are, in a very deliberate and unconscious level, exposed to all kinds of discrimination. And when somebody experiences it over time, they might start to believe that. Whether it’s conscious or unconscious. They might even accidentally collude with these discriminations and biases.

And so this idea of, that name is not of value because we can’t pronounce it. When I think about people who change their names or westernise their names so that others can pronounce it, so that it’s acceptable in our culture, we need to really ask ourselves, what are our deeper intentions and motivations why we change our name?

And so when I did change my name, yeah, you know, part of my internalised stuff started to come up. There’s a bit of a shame piece that I’m starting to feel in my body that I really need to check up on. With self-compassion and dignity. Be gentle with it and acknowledge that it’s there.

Joanne: So when you said internalised racism, like immediately my chest just kind of dropped and I was like, oh, that’s a term that I hadn’t thought about in a really long time. But really throughout like my own healing journey, you know, coming with parents that immigrated here from the Philippines who didn’t have access to mental health supports or really understood just the climate of being Canadian and what it meant to be a Filipino immigrant here in Winnipeg, I just feel like internalised racism really took root. Just even before I was born and really played an impact as to how connected I am or in my case, really not to Filipino culture. Is that something that you can also relate to?

Reece: I hear you in terms of, your own journey and I reflect on my parents’ history of immigration, migration, and the choices in where we lived originally. So I am born in Altona, Manitoba, which is a Mennonite community, for a number of folks who aren’t aware of it. We were one of the few families of colour that were there. And I don’t even remember growing up in my formative years with any people of colour around me, never mind Filipinos. And that being said, in my experience, my family did not teach me any of the dialects, any of our history, any of our culture. Didn’t expose me to traditional foods or textiles that just didn’t exist.

When we moved to Winnipeg in the ’80s, to my surprise, I saw coloured people for the first time. I couldn’t understand those coloured people and the differentiation between, for example, someone who is from Southeast Asia versus other countries of Asia to those who are from Africa. I couldn’t differentiate and I didn’t understand the dialect.

So when I remember my mother, laying with me when I was a young person, I think I was around six or seven years old. And she said to me, and I understand where she comes from. But she said to me how important it was for me and the family to blend. And to speak well. And to be seen and to have those jobs of being a doctor or being a lawyer or being a teacher — specific career roles that would help us to be seen as worthy.

Even my dating choices. There was a conceptualisation for my family who would be seen as worthy. And so growing up, I went with the flow. Because, of course, we would not go against our parents wishes. Or at least try not to, because it’s not just about our parents, it’s about our parents and our culture and our community.

And that’s something I learned to later on as part of, why this was really, really important. I just didn’t understand it. And so, I felt that the identity of being a Filipino wasn’t as important, and it was more important to assimilate. It was more important to blend, and it was more important to be successful financially, as well as from a career perspective, because they did not want me and my siblings to grow up the way they did.

And I get that. Now we’re looking at more of the historical pieces. But then if we go backwards even further and thinking about, well, where do they get that from? We can look at the roots of colonisation in the Philippines and how colonisation over and over and over again, diluted much of our history and created some confusion as to who is really a Filipino. And outside of Manila and Baguio and Tagalog and Ilocano, who is a Filipino.

What is truly Filipino culture. And that for some people really is an ongoing question. Even those who have migrated, if I were to ask a person, what does it mean for you to be Filipino? While the answers are rich and diverse, there is a bit of tenuousness with what that means for them and what the consequences are if one loses their roots.

And what are the consequences if their roots remain and reject aspects of Western culture. It can be very confusing for folks.

READ: A Filipino heart in Canada: Finding identity through history, legacy, healing

When I think about my history, I think about this concept called “third culture.” And a third culture dynamic or a paradigm is someone who straddles their home culture as well as a culture that they didn’t grow up in or their parents culture. So a sociologist by the name of Ruth Hill Useem in the 1950s, this sociologist really kind of looked at these two dynamics.

And so what many of us experience is, what does it mean to retain the roots of our home culture. What is our relationship in the culture that we live and the complexities of navigating the two? And when I hear stories of, I feel like I need to blend. In Western culture, there is a feeling or loss of identity or authenticity because it’s too risky. It’s too risky to be different. So as humans it’s in our DNA that we want to feel a sense of belonging. We want to feel a sense of inclusion, and we want to feel safe. And when that is not there, and this is a very human need, that we may give up parts of ourselves in order to fit in and feel that sense of belonging. Because being othered, has mental health consequences and cultural implications as well.

But I also often think about the mental health components of our mental health as Filipino people. What does that mean? I talk to Filipino folks and they would share like, my mental health is fine. And then when we go a little bit deeper when it comes to race-based components that impact mental health. What comes up for a number of people are these, like parts of grief. I have to give up parts of who I am in order to fit in this culture. And in this Western culture, which is very individualised, that it is all about the “me” rather than the “we.” And then straddling the home culture, which is — for our culture — it’s about the “we” and not necessarily about the “you.”

And if you focus on you, you’re deviating from the “we,” and we’re in this together. So if something were to happen to you, it happens to us. If something good happens to you, it happens to us. And we have each other’s backs that way. Except when you’re too different. So there is like a very, very, again, this kind of tension. And with that difference comes the stereotypes that I hear from Filipino individuals.

It’s the gossiping and the kind of like the shame and the little smirks here and there that meant to be teasing. But we’re not teasing. So know your place or know what to do because we know what’s going to happen when we deviate too far away from the expectations of cultures. Which doesn’t feel great.

And so I talk to Filipinos about, what does it feel like to be on the end of the gossip. I mean the work that I do, my last name, how I present my gender. All of these are ripe for teasing and shaming and gossip in our culture, which meant for me to back away from our culture, despite who I am or the work that I do and the impact of my work.

It ends up being a sacrifice of, I want to be a part of my culture, but I don’t think that parts of my culture, parts of our culture embrace me. So it’s a balance. And a really tricky balance.

Joanne: It’s heavily nuanced.

And I don’t know if this is your experience too, but for me growing up, it seemed that all of these things, these expectations and consequences, they were all sort of unspoken for me. It was like, oh, you just should know this. Growing up and not explicitly being told or taught, you’re just sort of trying to navigate and your nervous system is like, always on high alert because you don’t know until you experience it. And then you have to sort of navigate like, well, what does this mean? What did I do? And so for me, it was like all of these unspoken rules and then figuring out, oh, I navigate through this by making sure that I know the expectations, even if that means sacrificing parts of myself to please other people.

Reece: You know, and what’s hard in our culture is that we haven’t built yet a relationship, a healthy relationship for what it means to be vulnerable.

And what it means to speak authentically from our hearts and from our spirit, and that we are guarding from the histories of shame. These are legacies of colonisation and the histories of colonisation in our culture that want to suppress who we are. This is also part of white supremacy.

This is also part of patriarchy and all of those systemic issues that come with colonisation. Our culture also historically has not been given the tools to talk about being vulnerable. It’s almost like it’s an outlier when I meet Filipinos and Filipino families who have really deep, meaningful, vulnerable conversations. I see it as an outlier, not the norm.

But that takes a lot of work and a lot of risk to go there. And for some people, a lot of therapy, to understand that our culture has been suppressed so much that not only have we lost parts of who we are, but we needed, over years, to sacrifice those parts to now feel a sense of belonging and and camaraderie and kinship.

All that combination, that’s part of the language of shame. I’m not good enough unless, and don’t go there because that’s too risky, but I can’t speak about it because I don’t have the tools to do it. I just need to keep it together. Right? And that’s the overarching you know, what comes to my office, which is I need to keep it together and navigate all this in a culture where we don’t talk about this. And that’s hard.

Joanne: So hearing you say that brings up a lot of emotions because I think, just by nature of who I am, and growing up the way that I did, I am a very open and talkative person. Growing up in a turbulent household, I think I got really comfortable being uncomfortable. And so doing this special and talking to you about these very vulnerable and intimate things, that’s something that I not only want to do, but I really thrive in for not just healing myself, but hopefully healing other people.

That was literally the experience that I had growing up. I remember being in a huge fight with my dad, who’s no longer here, but, really wanting to talk about why we were so angry at each other. And there we were, standing in the kitchen, I think I was 17, very rebellious. And I just said, why can’t we talk about it? And he looked at me and, you know, we had been shouting at each other. And then the the moment just his voice dropped and he just said, ‘We’re Filipino and we don’t talk about it.’ And that is burned into my memory.

And I remember asking him why. So we were shouting and all of a sudden we’re talking in very hushed tones. We’re (standing) close together. And he was like, it’s just something that we don’t do. And so even moving from that, with my mom, who’s still alive, and my brother, who is a few years younger than me, we don’t connect at all. It’s very surface level and you know, pushing for therapy and, counselling.

But I think that it’s sort of outside of their scope at the moment, sort of facing their own shame. And just that inability to take the tools and know how to use them, I find. So when you say many of us have internalised shame, that resonates big.

Reece: Yeah. Internalised shame and a lot of fear. A lot of fear in terms of the what ifs, the what happens if. And what does this mean.

We do need to catch up in terms of really thinking about what tools do we need to have these vulnerable conversations. I don’t accept it anymore that we’re Filipino, we don’t go there. I cannot. I reject it. It was one of the reasons why I’m not close with my family of origin.

Because they don’t have the tools. I didn’t have the tools. I knew I was an angry kid. I didn’t understand why I was so angry until I became an adult and also really had the tools to critically think about this. And what I see in many different families is that we don’t have the tools to be emotionally accountable.

We don’t have the tools to say, I’m sorry, in a way that is deeply meaningful. We don’t have the tools to hold space for one another and what that means, and to feel empathy in a different kind of way. It’s empathy, but it’s empathy with a roadblock and a barrier.

Joanne: Conditions.

Reece: Yeah, that I’m not going to give myself permission to go there to be too empathetic with the person that I hurt because then it’s gonna remind me of my shame. It’s going to bring me back to the feeling of me being emotionally broken. And that’s a language that’s not being used.

So that gets me kind of emotional because growing up in my family, we never apologised to each other like that. I was gonna ask you: did your family ever apologise?

Joanne: No they didn’t. My dad and I (would scream at each other) and that was a normal thing. We went at each other quite often because I think we’re very similar, strong-willed and strong-minded people. I would hurt his feelings and I wouldn’t apologise. And neither would he.

Just even last weekend, I did say something that was quite harsh (to my partner). And I remember just sort of thinking about it, and I was like, I should apologise. But it took me hours to get there and sort of along with that, I’m like, why?

Reece: But also when we escalate in a conflict, the other way we can look at this is we just want to be seen. We want to be acknowledged. We want to be validated for our own deep personal experience. And when we don’t receive that, we’re going to fight for it. We’re going to escalate. And, that need so deeply to be seen, overarches an emotional accountability towards the other person.

And so I understand when these escalations within our cultures arise and nobody apologises. But then it’s common when things cool down, we’re just going to forget about it, and we’re just going to go about our business until the next escalation. But with every escalation, with every hurt that happens, that then becomes a part of grief. Multiple griefs that are in our heart and in our spirit.

We grieve thousands of times when we are not seen and we want and we want to be heard. And at the same time, if our families don’t have the tools to really, truly see us because they weren’t seen, we’re repeating now the legacy of colonisation. Because colonisation is about cultural genocide. And so if Filipinos, Filipinas, Filipin-x folks are not seen and not given tools to, we could see this happening.

So I wonder if what I just shared with you, how does that resonate for you.

Joanne: It resonates quite deeply. Because I remember all of these fights I had not just with my dad, but with my mom and my brother. And at the root of it, looking back at it, that’s what I want: to be seen and to be understood. Not even necessarily agreed with, but just understood.

And I think that is sort of my own legacy that I’m carrying forward. Even in daily interactions. I’m OK with different opinions. But if somebody doesn’t take the time to truly understand where I’m coming from, and the different needs that I have in terms of positive interactions and demonstrating how we respect each other, it’s a huge point of contention for me.

CityNews Connect: A Filipino Heart in Canada

Reece: One of the things I think is going to be helpful for us as Filipinos is to give ourselves permission to lean in to the other and hold our truth and be grounded by it, but approach one another with curiosity. It’s easy for us in our own traumas to listen to somebody, but then go right into comparison.

Your experience versus my experience. And I want to hold that truth for you and acknowledge that truth for you, even though that isn’t my experience. That isn’t my lived journey. We need the skills and how to do that. We just don’t right now. Or many folks don’t. Culturally we don’t. I could say that overarching culturally, that’s that part where, I hope that, with your work, my work, a lot of us that we can move our cultures in a way where we can learn to see one another. Be curious with each other, hold space for one another, meaning that, we can be each other’s safe container, regardless of where we come from. You know how Filipinos get together with other food around the table and everything? That we can all be around the table and share a beautiful meal together and ask meaningful questions, because we really want to get to know the person deep down without any judgement. But again, with this welcoming, loving, heart to heart curiosity, even though it’s not our lived experience.

I know that most likely that’s not going to happen (for me). So I had to grieve that. But I also had to find the closure in knowing that I understand why that is. Now what is my ethical and moral obligations so that future generations are not going to continue the legacy of the traumas that our families endured and led them to where they are, and their relationship with shame.

So the more we understand those journeys, we can hopefully find the closure, not to say that we’re not going to be sad, not to say that we’re going to feel it in our bodies and in our minds and in our hearts — of course, we’re going to continue to feel that. But we can do it with deep compassion so that we can gently, in a sense, not close the door but look through the window and understand where that is, where that comes from, so that we can make discernible choices and how we want to show up for other people.

One of the things that’s important is to recognise that the intentions of our families doesn’t equate to the outcomes. The intentions, if we had to really look at where are the intentions of our families — why do you see these negative, toxic things — is because they’re well intentioned. They want us to succeed. But the underlining of it is that shame.

And if we look at it collectively as a culture, we’re talking about cultural shame. If we’re talking about where it comes from, we’re talking about systemic shame, intergenerational shame from those original messages and what makes success and what doesn’t. And I think we do need to come together. First, let’s name it as a culture.

We gotta name it as valid. And for some people, some Filipinos I speak with it, there’s these eureka moments. What you said now names what I am experiencing, but never had the tools or the language to express. This is what’s really going on. Language is powerful. You and I know that language is powerful.

And when we’re able to name it with integrity and dignity, love and compassion, we can move forward as a collective culture that maintains our identity. And rather than, something that you named as, taking the best of our history, I like to conceptualise it as a return back to our history. A turn back to our ancestry that honoured the differences where we can collectively and individually, we call this interdependence of one another, that we collectively and individually, we can cry together.

We can laugh together. We could be vulnerable together. Our creativity is honoured, just and valued, just as medicine. That our spirituality is just as loved and admired as our brain.

We need to really look at this and do the return and to recognise, are we replicating, quite frankly, cultural genocide by not honouring our ancestors and not honouring our ancestors’ values and principles when it comes to who we are as Filipinos?

We’re doing the best that we can to live in a culture here that doesn’t encourage us to go back to it. It discourages us and wants us consciously, unconsciously, intentionally and unintentionally to shed our own roots and for us to emerge as something else altogether. Independent from this. And so when I think about what you just said about being disconnected, I mean, the opposite is true. Have our cultures disconnected from us just as much as we disconnected from them?

I wonder if culture means community. And what people really mean is you’re not connected with community. Yeah. OK. And so I can say I’m not connected with community. I could go to Kildonan Park and look at all those big Filipino families and walk with my dog and my husband and feel that I’m not invited.

And so as I walk back and forth and I’m smelling the richness of our food, it’s like, oh, I just wish someone could just be like, hey, come join. Come eat and have that invitation. So it’s a kind of call to action for our culture, which is, why not bring others in that may be like us? Or are similar to us as part of building community.

I’m reconceptualizing what it means of not being part of the culture. I think you’re part of the culture. I think how we do culture, especially as first generation Canadians, may look different than those who migrated. And first, second and third and even fourth generation Filipinos, how they do community and culture is going to look so different than you and I.

Joanne: For people that are going to be watching this. What are you sort of hoping that they take away from this conversation that we’ve had?

Reece: I hope that people leave with being curious. Thinking about what it means to be compassionate. Thinking about that what one is feeling inside, may be a legacy of colonisation and the shame and embarrassment. The needing to fit in or not step out is a by-product of colonisation. That shame is trauma. That we are of value.

All of our contributions matter. That vulnerability is a strength that we need to lean into. It’s not a weakness. It’s part of our humanity. And that we find the courage to reach out to each other, including myself. Even though we’ve endured a lot of pain and struggle. And that we connect with one another, to acknowledge our own grief, our collective grief, and so that together and individually we could find closure.