More than meets the rink: Behind the scenes at the `72 Summit Series with ‘Ice War Diplomat’ Gary Smith

Posted December 18, 2022 6:43 pm.

For hockey fans of a certain vintage, no tournament has the stakes or the drama of the 1972 Summit Series between Canada and the Soviet Union. And while the collective memory of the tournament has been whittled down to moments like Paul Henderson’s iconic game-winning goal that ended the series, there is much more to the story than meets the eye, or in this case, the rink.

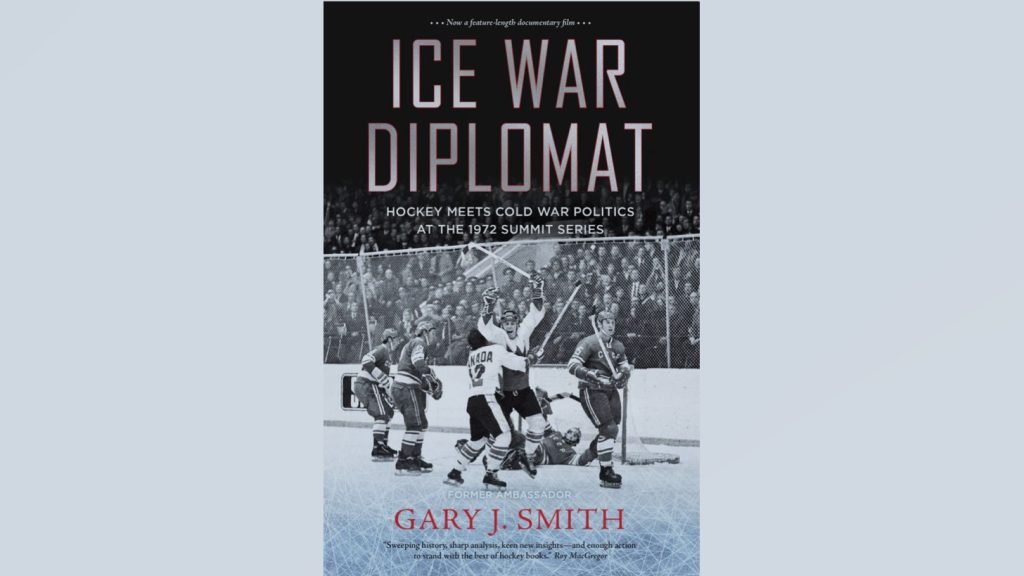

Now, 50 years on, that story is being told for the first time in Ice War Diplomat: Hockey Meets Cold War Politics at the 1972 Summit Series by author Gary J. Smith.

John Ackermann: Now, it’s said you were instrumental in making the tournament happen – and keeping it from falling apart. That’s quite the big job for a 28-year-old officially tasked as the Canadian government’s liaison officer and interpreter.

Gary Smith: Well, I was a young Canadian diplomat in Moscow. I had spent a year learning Russian day after day, week after week, month after month, and I was sent to Moscow just ahead of [Prime Minister] Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s visit. He wanted to reduce tensions with the Soviet Union, make sure there wouldn’t be a conventional war or nuclear war, and so he was looking for common ground. My job at the embassy was to work on exchanges. And what better common ground was there than hockey? We had scientists, educators, musicians, theatrical people. But if you wanted to reach the far areas of the Soviet Union and go down into society, you needed something that would be appreciated by everybody in Russia. So, they love hockey over there just as much as we do here. And that seemed the way to go about it.

Read More: Former NHL tough guy wants to unleash the fighter in all of us

[Canada] hadn’t won an Olympic game since 1952 with the Guelph Mercurys and we hadn’t won a World Championship since `61 with the Trail Smoke Eaters. We were desperate to show the Soviets that we had better hockey players, but we couldn’t get the NHL [players] to be allowed to play. The Olympic Committee and the International Ice Hockey Federation said you had to be an amateur. Somehow, they figured that the Soviets, who all work for the army, were amateurs whereas our guys weren’t.

So, what we did is we came up with an arrangement to have an exhibition series, no trophy or anything, four games in Canada, four in the Soviet Union, and to have best-versus-best. And I was involved in almost all in negotiations that led up to that. I travelled with the Soviet team to Canada for the four games here: Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Vancouver, and then I was with Team Canada in Moscow. And, as you can imagine, there are lots of times when the series was going to go off the rails. And my job I was told by the people in Ottawa, “Your job Gary: make sure that this series gets to the end.”

Ackermann: The book lays out a lot of the behind-the-scenes intrigue in setting up the tournament. Indeed, it opens with fraught negotiations about the referees for the eighth and final game. Was there ever a moment where the fate of the whole tournament was in jeopardy?

Smith: Well, it was the debate over the referees before game eight because Al Eagleson and Harry Sinden said they weren’t going to play if the West German referees were on the ice. We spent hours and hours and hours negotiating this and eventually we said we would each choose one referee and we chose the Swede, Ove Dahlberg, and then we were told he was sick. But we had had breakfast with them in the morning. That turned out to be a political illness. So, there was the chance the series wouldn’t have had the game eight. Also in Montreal, a Canadian had had his car crushed by a Soviet tank in Prague, Czechoslovakia in `68 and he put a lien on the Soviet equipment. So, there was a chance that the Soviets wouldn’t have had any equipment to play in the game. So, there are a number of incidents where this series may not have happened even after we had negotiated the arrangements for it.

Read More: NHL legend Bryan Trottier reflects on family and Indigenous roots in new memoir ‘All Roads Home’

Ackermann: You could say there is a political legacy and a hockey legacy to the Summit Series. The hockey legacy seems to be the opening of the NHL to more foreign players and a change to a more European style of play. How does it feel to have been a part of that?

Smith: Well, it feels great because at the time in 1972 about 98 per cent of the NHL players were Canadian. Today, we’re down to around 43 per cent. So, hockey is really internationalized. The other thing that series did was, you know, nobody really trained during the summer. Hockey players sort of drank beer and sold beer. The idea that you had to have a diet as an athlete, that wasn’t common practice at the time. And when we saw the Soviets play, we realized, “Gee, these guys are in great condition.” And we learned that diet is important for athletes, year-round training, dry land training — particularly running. And all those things came back to Canada. There was a Canadian coach called Lloyd Percival, who had written this out [in The Hockey Handbook] in the early `50s. We didn’t pick it up, but the Soviets did, and they used a Canadian technique to train their players up so that they were in terrific shape.

Read More: He owned the night: Dan Russell looks back at 30 years of Sportstalk in a new memoir

Ackermann: When you talk about the political legacy in the book, you talk about this power of teamwork concept. Do you think hockey can build bridges between East and West again, as it did in 1972?

Smith: I think it’s possible. You know, the invasion of Ukraine, it’s a terrible situation. We were going to have all kinds of ceremonies this year to celebrate the 50th anniversary. Russian players were going to come here, we were going to go over there and so on, but all that got scrubbed. A lot of the junior games have been cancelled, the international tournament in St. Petersburg next spring is cancelled. But there’s still around 55 Russian players in the NHL and many of them are stars of the game right now. And so, I think it still is a bridge, still a way for us to connect to Russians. We’re going to have to deal with Ukraine one way or another, militarily, politically, as time rolls along here.

You know, I mentioned that Canada ground to a halt in September of 1972. Everybody in this country wanted to see this series. But at the same time, we estimated that there were 150 million Soviet citizens who watched the series on their televisions, so it has a great appeal, it is something that we have in common with the Russians. I was back last year; I was back five years ago. They’re still talking about this series. They know all the Canadian players from 50 years ago, so it had a massive impact, and it still does, and I still think the hockey bridge, even though we’ve had tanks going over it, is still a vehicle for us to improve our relations and have some common ground with the Russians.

Read More: Celebrating a century of BC sports memories

Ackermann: How do you want the Summit Series to be remembered and what do you hope people get out of the book?

Smith: People say it was the greatest hockey series ever, the greatest moment in Canadian sport when Paul Henderson scored with 34 seconds to go, team of the century. It was the first time that [the name] Team Canada was used. We never called our teams Team Canada before that. And now, every international team we have, whether it’s soccer or basketball or whatever, is Team Canada. It was a moment where we reached out, we thought we were really great, we were humbled in Montreal, we were humbled in Vancouver, but we came back. And that spirit of coming back and digging deep and not giving up to the very end, I think is one of the greatest legacies of that series.

Ice War Diplomat: Hockey Meets Cold War Politics at the 1972 Summit Series is available from Douglas & McIntyre.