Bishop Grandin’s name to be removed from Winnipeg roadways ‘in the coming months’: Mayor Gillingham

Posted March 23, 2024 5:54 pm.

Last Updated March 25, 2024 2:12 pm.

It’s been one year since Winnipeg’s city council unanimously voted to remove Bishop Grandin’s name from several roadways in the city.

And while the old signs are still up, Mayor Scott Gillingham says it’s only a matter of time for the new ones to take their place.

“We’re getting closer to the days when the signs are gonna go up,” he told CityNews, confirming the decision has not been postponed. “Residents, motorists will see that change soon in the coming months.”

Last March, members of Winnipeg’s Indigenous Relations Committee voted to rename Bishop Grandin Trail, Bishop Grandin Boulevard and Grandin Street. Their namesake, Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin, is known to have played a significant role in the development of residential schools in Canada.

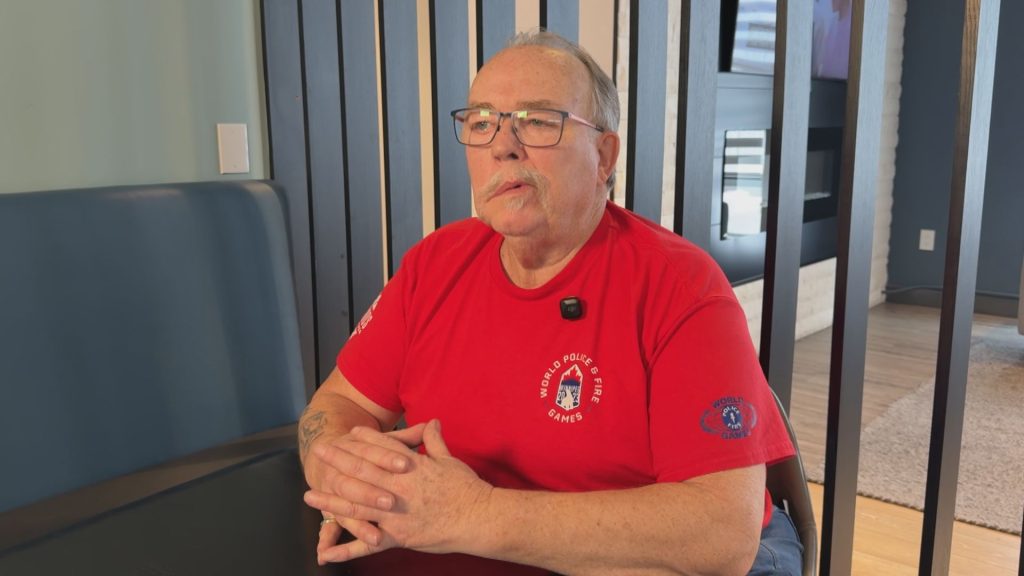

“I know lots of people didn’t believe that the name’s actually gonna be changed because it’s been so long,” said Kyle Mason, an Indigenous speaker and consultant. “They thought it was a token gesture, or somebody wanted to make the news that particular day. But it’s nice to know that it’s finally going to happen.

“Most Winnipeggers are still calling it Bishop Grandin, which is not accurate.”

Bishop Grandin Trail will be renamed Awasisak Mēskanow; Bishop Grandin Boulevard will be called Abinojii Mikanah (which means “children’s way” in Anishinaabemowin); and Grandin Street will be known as Taapweewin Way (which means “truth” in Cree).

“It’s really about our journey of reconciliation as a community, which is really important, not only today, but to the future as well,” Gillingham said.

“It honours Indigenous children, First Nations children, who really in many ways bore the brunt of what was done in the past tragically in our nation.”

Mason says the renaming in honour of children means a lot to him as someone who has been impacted by Canada’s legacy of separating Indigenous families from their children.

“We’ve lost hundreds of thousands of children to colonization and to the attempted genocide of our peoples, so it’s nice to know that the history is going to be remembered and that different things are going to be appropriately named after the children who survived and the children, sadly, who did not survive,” he said.

Mason’s father was a survivor of what he calls a “residential institution,” refusing to call it a school because “these were anything but schools.”

“My father was deeply impacted in a negative way, to the point that much of his life he was unable to be a healthy man or a healthy father, or a healthy husband. He was deeply hurt and he passed a lot hurt onto a lot of people. Thankfully, he did a lot of healing and a lot of recovery and tried to make amends with as many people as possible before his passing. But it deeply impacted his life, therefore deeply impacted my family’s life, impacted my life.

“Now, I’m trying to make sure that the legacy of these institutions, the harm, the intergenerational trauma, comes to an end with my generation and is not passed down to my young son.”

The Indigenous speaker say the original act of changing Indigenous names is a “very colonial way of thinking.”

“When the settlers got here, everything already had a name,” he explained. “So it’s nice to know that some of the names are finally gonna respect the original peoples of this land.”

Mason argues the changes are long overdue and he’s ready to see the signs go up.

“It’s nice to know that this major roadway in Winnipeg will no longer be named after a monster, somebody who was racist and wanted to eradicate our peoples from this land,” he said. “It’s nice to know that some of our names are finally gonna be respected more and more throughout this land.

“So when we know better, we need to do better. That’s what this is all about.”