‘Epidemic levels’: Perpetual funerals leave Canada’s Indigenous in constant state of grief

Posted February 27, 2024 7:33 pm.

Last Updated February 27, 2024 9:13 pm.

Many Indigenous people say going to funerals regularly is a sad reality for the community, but what’s more of an alarming trend is the number of funerals being held for young people.

Former Grand Chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakinak Sheila North says she’s been to five funerals since December – with another one possibly upcoming.

“It’s so sad,” North said. “I just got a notice today that one of my childhood best friends is burying her young daughter on Friday… it hits home quite a lot.

“The last few months, some of my best friends losing their young people, their children at such young ages. It’s terrible.

“Our elders and our family members who have to say goodbye to younger relatives, it’s so heartbreaking and it’s almost reminiscent of Residential School days when parents and grandparents had to lose their family members to Residential School systems and say goodbye, almost forever in many cases.”

The former Grand Chief calls it a “crisis” that is having tremendous impacts on communities “all across our country.”

“There are many reasons that people are passing away, but I can definitely say that they have been untimely,” North said. “The mortality rate is so much younger for Indigenous people that are passing away and it’s very alarming.”

North says too many times, children are having to deal with death at a very early age.

“Little children having to peer over the coffins to see their loved ones is so heartbreaking,” she said. “It’s a reality here that we’re feeling among our families.

“It’s having a huge impact on our future generations, not only in terms of people passing away – that’s a huge tragedy – but the mental strain that is going to cause on our future generations and our current generations.

“I feel the strain on our families. I feel the pain of our families.”

North says many in the community can never escape the grieving process.

“Once we are finished saying goodbye to one loved one, we’re preparing for another one,” she said. “So many deaths are overlapping over and over and we never get a chance to process it properly as families or as community of the magnitude of the losses.

“The crisis situation and the grieving process never seems to end. It’s an ongoing feeling in our community.”

Matthew Shorting lost his first close friend when he was 21 years old. He said some in his family were surprised he made it to adulthood before being impacted by a young loved one’s death.

“There’s definitely a numbing, being numb,” Shorting said. “I don’t even want to go to funerals, to be honest. We have celebrations of life sometimes, so I like those. But just preparing for it, it takes a lot of emotional energy to see the whole family grieving, and loss. It’s heavy.”

“I cannot believe all the people we don’t get to grow old with. I’ve been to more funerals than I have been weddings or graduation ceremonies.”

—Community member Matthew Shorting

Shorting says there’s a reason so many deaths continue to happen, and it can be traced back through Canada’s history.

“With the backdrop of colonization, forced relocation, cultural suppression, it has created adverse environments,” he said. “And in the adverse environments we’ve had health disparities, we haven’t had the same quality of care and our infrastructure… there’s also lots of detriments of health, poverty.

“And this has contributed to people’s mental health, their skills and ultimately in the end it’s contributed to violence and safety issues. There’s a line, a connection from history up to the present moment. We didn’t just get here by ourselves.”

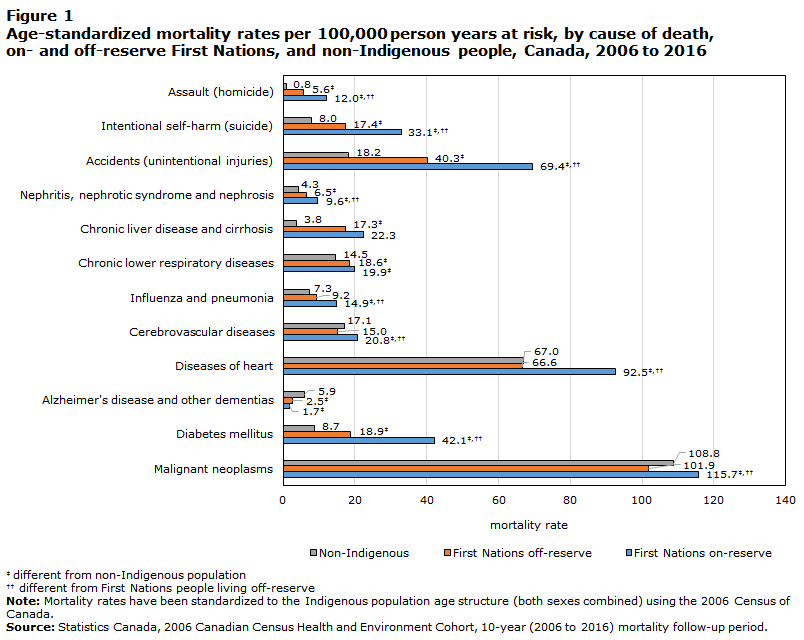

Studies by Statistics Canada support Shorting. First Nations people, both on and off reserve, frequently have much higher mortality rates than non-Indigenous people.

“It’s reaching epidemic levels. It’s a crisis,” North reiterated. “We need to provide better solutions that come from our communities on what needs to be done.”

North says she heard an anecdote several years ago that she feels may even be underestimating how common death is in the community.

“I heard… that we go to maybe 100 funerals in our lives but non-Indigenous people go to maybe 10 in their whole lives,” she said.

North says it’s crucial the needs of Indigenous people are prioritized throughout all forms of government: municipal, provincial, federal and local First Nations.

“We have to start prioritizing better health outcomes because we are forgetting that sometimes, while we are trying to do everything else, we forget to do the basic things, such as offer the help that families need for basic health,” the former Grand Chief said. “It’s all about basic human rights that are being violated in many cases when people don’t have access to proper health, even clean water, good food, sustainable living.

“We’re causing huge ripples of trauma when we continue this attitude towards in Indigenous people in our own country.”

North believes a source of hope, while it may be “hard to find” sometimes, comes from family and communities.

“Because we have forgotten the value of our people sometimes,” she said.

Shorting feels hope can come in different forms.

“My culture gives me hope,” he said. “My child gives me hope. Future generations give me hope. I have to exercise my mindset for that hope, too, because I can easily lose it.”

Hope, he believes, can even be found in times of funerals.

“Something that was shared with me when I lost a family member to suicide was to live my life the best way I could for them, to make them proud,” Shorting said. “That they would want a good life for you. So there needs to be a message of hope for people who are losing loved ones.”