With AI, workplace surveillance has ‘skyrocketed’—leaving Canadian laws behind

Posted March 9, 2024 5:00 am.

Technology that tracks your location at work and the time you’re spending in the bathroom. A program that takes random screenshots of your laptop screen. A monitoring system that detects your mood during your shift.

These are just some ways employee surveillance technology — now turbocharged, thanks to the explosive growth of artificial intelligence — is being deployed.

Canada’s laws aren’t keeping up, experts warn.

“Any working device that your employer puts in your hand, you can assume it has some way of monitoring your work and productivity,” said Valerio De Stefano, Canada research chair in innovation law and society at York University.

“Electronic monitoring is a reality for most workers.”

Artificial intelligence could also be determining whether someone gets, or keeps, a job in the first place.

Automated hiring is already “extremely widespread,” with nearly all Fortune 500 companies in the United States using AI to hire new workers, De Stefano said.

Unlike traditional monitoring, he added, AI is making “autonomous decisions about hiring, retention and discipline” or providing recommendations to the employer about such decisions.

Employee surveillance can look like a warehouse worker with a mini-computer on their arm that’s tracking every movement they make, said Bea Bruske, president of the Canadian Labour Congress.

“They’re building a pallet, but that particular mini-computer is tracking every single step, every flick of the wrist, so to speak,” Bruske said.

“They know exactly how many boxes are being placed on that pallet, how much time it’s taking, how many extra steps that worker might have taken.”

There is little data documenting how widespread AI-powered worker surveillance might be in Canada. Unless employers are up front about their practices, “we don’t necessarily know,” Bruske said.

In a 2022 study by the Future Skills Centre, the pollster Abacus Data surveyed 1,500 employees and 500 supervisors who work remotely.

Seventy per cent reported that some or all aspects of their work were being digitally monitored.

About one-third of employees said they experienced at least one instance of location tracking, webcam or video recording, keystroke monitoring, screen grabs or employer use of biometric information.

“There is a patchwork of laws governing workplace privacy which currently provides considerable leeway for employers to monitor employees,” the report noted.

Electronic monitoring in the workplace has been around for years. But the technology has become more intimate, taking on tasks like listening to casual conversations between workers.

It’s also become easier for companies to use and more customized to their specific needs — and more normalized, said McGill University associate professor Renee Sieber.

De Stefano said artificial intelligence has made electronic monitoring more invasive, since “it is able to process much more data and is more affordable.”

“Employer monitoring has skyrocketed” since AI has been around, he added.

Those in the industry, however, insist there’s also a positive side.

Toronto-based FutureFit AI makes an AI-powered career assistant, which CEO Hamoon Ekhtiari said can help individuals navigate workplaces that are being rapidly changed by the technology.

AI can look for jobs, give career guidance, look for training programs or generate a plan for next steps. In the hiring process, it can give applicants rapid feedback about gaps in their applications, Ekhtiari said.

As artificial intelligence permeates Canadian workplaces, legislators are making efforts to bring in new rules.

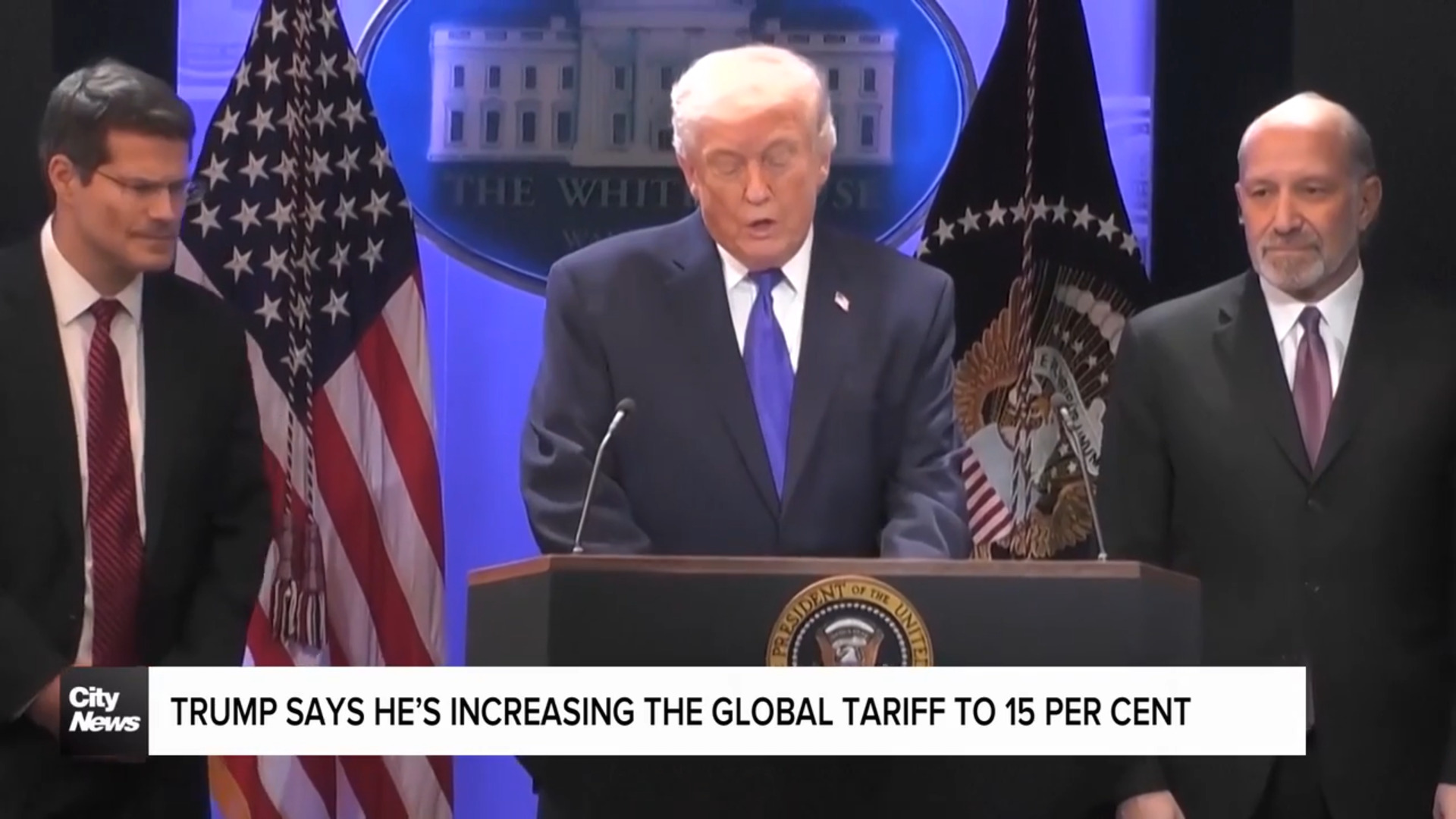

The federal government has proposed Bill C-27, which would set out obligations for “high-impact” AI systems.

That includes those dealing in “determinations in respect of employment, including recruitment, referral, hiring, remuneration, promotion, training, apprenticeship, transfer or termination,” said Innovation Minister François-Philippe Champagne.

Champagne has flagged concerns AI systems could perpetuate bias and discrimination in hiring, including in who sees job ads and how applicants are ranked.

But critics have taken issue with the bill not explicitly including worker protections. It also won’t come into effect immediately, only after regulations implementing the bill are developed.

In 2022, Ontario began requiring employers with 25 or more employees to have a written policy describing electronic monitoring and stating for what purposes it can use that information.

Neither the proposed legislation nor Ontario law “afford enough protection to workers,” De Stefano said.

Activities like reading employee emails and time tracking are allowed, as long as the employer has a policy and informs workers about what’s happening, he added.

“It’s good to know, but if I don’t have recourse against the use of these systems, some of which can be extremely problematic, well, the protection is actually not particularly meaningful.”

Ontario has also proposed requiring employers to disclose AI use in hiring. If passed, it would make the province the first Canadian jurisdiction to implement such a law.

Provincial and federal privacy laws should offer some protections, in theory. But Canada’s privacy commissioners have warned that existing privacy legislation is woefully inadequate.

They said in October “the recent proliferation of employee monitoring software” has “revealed that laws protecting workplace privacy are either out of date or absent altogether.”

Watchdogs in other countries have been cracking down. In January, France hit Amazon with a $35-million fine for monitoring workers with an “excessively intrusive system.”

The issue has also been on the radar for unions. The Canadian Labour Congress isn’t satisfied with Bill C-27, and employees and their unions have not been adequately consulted, Bruske said.

De Stefano said the government should “stop making the adoption of these systems the unilateral choice of employers” and instead give workers a chance to be fully informed and express their concerns.

Governments should be aiming for something that distinguishes between monitoring performance and surveillance, putting bathroom-break timing in the latter category, Sieber added.

A case could be made to ban some technologies outright, such as “emotional AI” tools that detect whether a worker in front of a computer screen or on an assembly line is happy, she said.

Emily Niles, a senior researcher with the Canadian Union of Public Employees, said AI systems run on information like time logs, the number of tasks completed during a shift, email content, meeting notes and cellphone use.

“AI doesn’t exist without data, and it’s actually our data that it is running on,” Niles said.

“That’s a significant point of intervention for the union, to assert workers’ voices and control over these technologies.”