Indigenous athletes get rookie hockey cards decades later

Posted January 25, 2023 6:41 pm.

Indigenous hockey players who never got rookie cards when they played, now have them decades later.

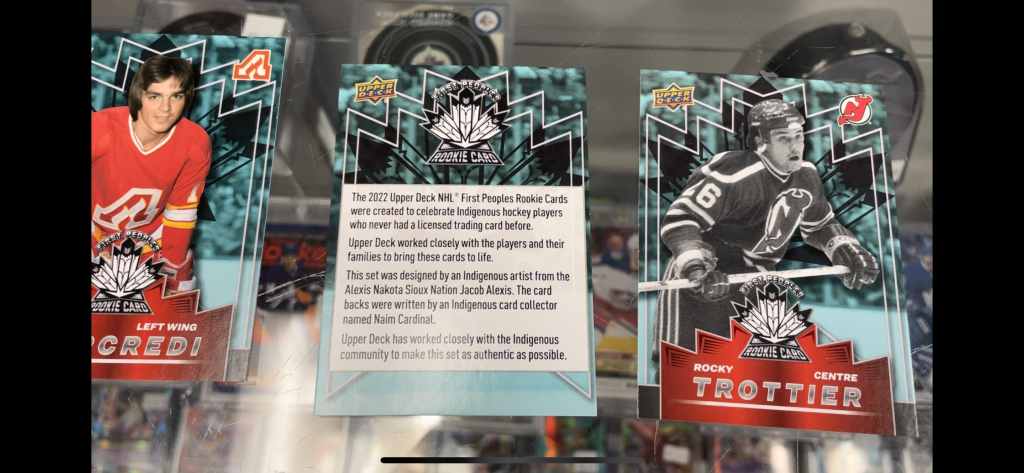

Upper Deck this month unveiled a “First Peoples Rookie Cards” set featuring eight Indigenous hockey players who did not get this opportunity the first time around. It comes at a time when appreciation for Native American and First Nations influences in the sport is on the rise.

An Indigenous-owned shop in Winnipeg that showcases Indigenous athletes is the only place you can get them.

“For the younger fans, to be able to read about these guys and just get inspired and know who helped paved the way for the players who play today for our communities – it’s really cool,” said Curtis Howson, who runs First Row Collectibles.

Indigenous hockey cards

But if you can’t wait to open the pack… you’re not alone.

“We got 500 sets last Wednesday, they’ve all been given out. We gave them out for free here in the shop. We also shipped out some sets to remote communities up north that just weren’t able to get to the shop – it was important to get the sets in the hands of those people because they deserve them as well,” explained Howson.

When Howson and his business partner got the opportunity to be the only retail location to dole out the Upper Deck First Peoples Rookie Cards – they jumped at the chance.

“To see those names, I was very inspired – very happy to see there were people from my own community and culture represented in the NHL. And now to see it as a set, it’s very exciting.”

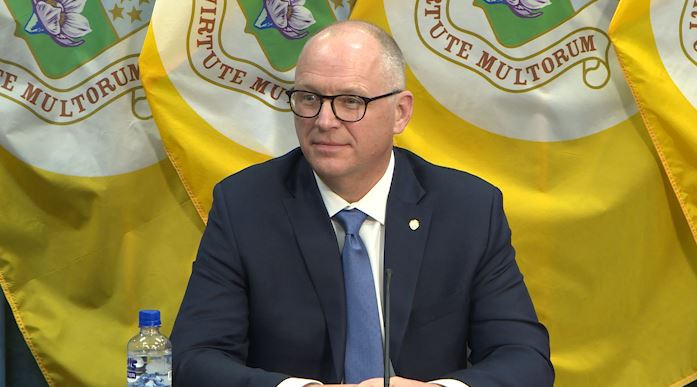

One person who hasn’t been able to get his hands on a Ted Nolan card, one of the eight players featured… is Ted Nolan himself. The former player and head coach of the Buffalo Sabres says the representation these cards bring cannot be understated.

“It’s really, really important to see someone like you, who grew up in a community like you – who grew up in a community like you, that went through some of the obstacles you’d go through. I’m honoured, I’m really honoured,” said Nolan.

Former NHL coach and player Ted Nolan.

“It’s kind of like somebody calling you 40 years after your 18th birthday and saying, ‘Hey, you’re turning 18,’” Nolan said. “It wasn’t as exciting as it would have been if I was actually getting it when I was a rookie, but just the same I’m so honoured to receive it, especially with the Indigenous component to it because (for) a lot of our kids, representation really does matter, and the more the kids get to see these type of things happening, they can dream, also.”

The idea behind the set came from Naem Cardinal in B.C., and the artwork was done by Jacob Alexis in Edmonton.

“We thought that was an interesting concept,” Upper Deck senior marketing manager Paul Nguyen said. “So, we asked other people within the hockey community to see if there was an appetite for a set like this, and we heard yes.”

Nolan credits them for inspiring a set of cards that are sure to inspire indigenous youth, at a time Nolan says, is crucial.

“Because of what we’re going through with residential schools, and all the trauma issues our people are going through – we need some positive things every once and a while. To be part of a positive thing like this, I’m thrilled, and I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for our elders and former chiefs who paved the way,” explained Nolan.

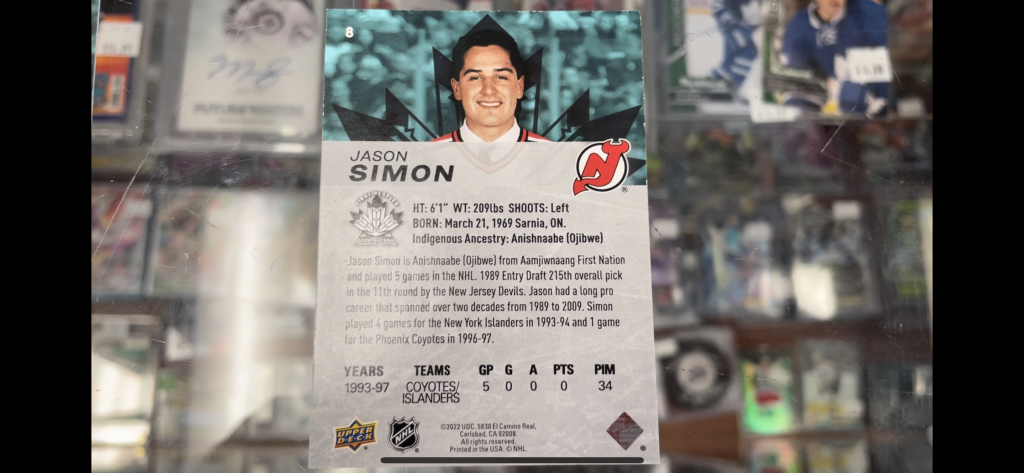

Jason Simon hockey card

The owners of First Row hope that Upper Deck sees the desire for more indigenous player cards, and creates a second series.

A group made up mostly of Indigenous community members worked to narrow the possibilities to players who never before had an officially licensed NHL trading card. The result is a set featuring Nolan, Dan Frawley, Jason Simon, Bill LeCaine, Rocky Trottier, Victor Mercredi, Danny Hodgson and Johnny Harms.

The cards, including the logo on each of them, were designed by artist Jacob Alexis from the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation, while Cardinal wrote the content on the back that highlighted the player’s Indigenous heritage and family history.

Nolan’s card, which shows him in a Detroit Red Wings uniform, points out he’s Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) from Garden River First Nation in Ontario and not only played in the NHL with the Red Wings and the Pittsburgh Penguins but went on to become a successful coach and has two sons who made the league, Jordan and Brandon.

Having a rookie card like his sons is a cool development for Nolan, who said, “It’s kind of like a family thing.” Taking it a step further, the cards won’t be sold but rather distributed at the 3NOLANS First Nation Hockey School and other Indigenous hockey camps and events.

Nolan hopes that showing kids the cards has a similar effect on them as watching the likes of Stan Jonathan, Gary Sargent and Jimmy Neilson did on him when he was growing up.

“You can kind of walk around school the next day and be very proud of those gentlemen (because) even though we didn’t know them, they looked a lot like you,” he said. “Now, not only can you talk about it. You can actually show pictures that it really did happen.”

Hockey historians in recent months and years have begun to delve deeper into the role of some of hockey’s first nonwhite pioneers, including Native American defenceman Taffy Abel and Henry Elmer “Buddy” Maracle.

Indigenous hockey cards

After more details have come to light about Canada’s history of boarding schools used to push First Nations children to assimilate to white culture from the 19th century through the 1970s, Nolan is proud to be an example of an athlete who embraces his Indigenous heritage.

“We had a lot of our elders and a lot of our chiefs that showed the way for us, and especially the survivors of the residential schools and how hard they fought to maintain who we are,” said Nolan, who coached parts of six NHL seasons and won the Jack Adams Award as coach of the year in 1996-97. “I’m just another part of that, trying to build on that legacy of our forefathers and make the next generation even stronger than this generation.”

Nguyen said this card set has been years in the making and pointed out it comes at a good time given the dialogue going on, especially in Canada, about the treatment of Indigenous peoples and what can be done now to learn from it.

“It’s continuing the conversation with everyone and it’s not just letting it kind of lie,” he said. “It’s putting it in a really good light where people can have that conversation.”

-With files from the Associated Press