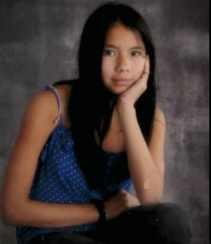

Tina Fontaine asked for help before she died: children’s advocate

Posted March 12, 2019 11:18 am.

Last Updated March 12, 2019 7:26 pm.

This article is more than 5 years old.

SAGKEENG FIRST NATION, Man. _ A report into the death of a Manitoba Indigenous teenager says she asked for help in the weeks before she was found dead in the Red River, but social agencies told her there were no beds available.

The report by Manitoba children’s advocate says that essentially left Tina Fontaine homeless and at risk for sexual exploitation.

“Tina had acute mental health needs following her father’s death but she was never provided with a single counselling session or other cultural healing, despite ongoing assessments and recommendations that this was a critical need in her life,” reads the reports from Daphne Penrose.

“Further, Tina developed acute addictions in her final months of life and used many different drugs and alcohol but was unable to find the help she needed that would support her to address her underlying pain.”

READ MORE: System failed Manitoba girl returned to parent without support, checks: advocate

Social workers and others ignored multiple signs that Tina was spiralling downward and in danger according to the report.

Penrose said following the death of Tina’s father, victim services did not follow through with the child to provide counselling support, “despite her right to this services and the obligation of victim services to provide it during the two and half years in which they were involved with Tina’s family.”

The child advocate’s report also looked into the sexual exploitation of the province’s youth–something Penrose says Manitoba has a “shameful reputation for”.

READ MORE: Small things become scary, says Indigenous teen of Fontaine case, MMIWG

The report also details how Fontaine’s family was affected by a history of residential schools, the ’60s Scoop, and child-welfare agencies.

“She carried a burden that was not her own,” Penrose said.

Tina’s mother was 17 years old and was still a child in care when Tina was born on New Year’s Day in 1999. Both her parents struggled with addictions.

Five years later, her father asked Tina’s great-aunt Thelma Favel to take care of her and her sibling on the reserve northwest of Winnipeg. It was a relatively stable time in the young girl’s life.

That changed when Tina’s father was murdered in 2011. Tina’s caregiver tried to get help for the young girl from victim services. But because of questions about who was the teen’s legal guardian, she never received counselling.

In June 2014, Tina left to try to reconnect with her mother in Winnipeg. When Favel didn’t hear from the girl, she called Child and Family Services for help.

The report outlines how Tina’s high-risk behaviour rapidly escalated in her final two months. She disappeared, was homeless, developed addictions and was sexually exploited.

But she also reached out several times for help.

On one occasion Tina called Child and Family Services but no one arranged to pick her up. Workers told the teen to ride her bicycle to a shelter.

There’s no evidence she arrived.

The report says Tina disclosed to her child-welfare agency that she was hanging out with a 62-year-old, meth-using man. Court heard during the second-degree murder trial of Raymond Cormier–who was acquitted last year in Tina’s death–how the young girl was associating with the older man and he admitted he was sexually attracted to her.

Social workers believed Tina had been sexually assaulted, but the agency still dropped the teenager off with a contracted care worker at a downtown hotel. Tina walked away from the hotel shortly after.

Just days later her 72-pound body, wrapped in a duvet cover and weighed down by rocks, was pulled from the Red River.

Recommendations from the Child and Youth Advocate

Penrose makes five recommendations which she says need to be acted on quickly because children and youth are still facing the same risks and getting the same responses as Tina.

The first is for Manitoba Education and Training to reevaluate the use of suspensions and expulsions in public schools. Penrose pointed to the recently-formed Commission on Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education which carefully examines the uses of those punishments so they can be limited, reduced, and phased out.

READ MORE: ‘Don’t talk to each other’: Inside Manitoba’s child protection hearings

The second recommendation is for Manitoba Health, Seniors, and Active Living which, ten months after the province handed down a mental health and addiction strategy, has yet to reveal implementation plans.

Penrose has also recommended for Manitoba Justice – Victim Services to “address the quality control measures that were lacking” in their interactions with Tina and her family. “While this system was involved for a number of years, barriers to access the service were plenty and overall, the service was not delivered to Tina in child-centred ways.”

The next is aimed at Child and Family Services and its responsibility to kids in need of protection.

READ MORE: ‘Traumatic to witness a lack of empathy’ says mother of apprehended newborn

“What Tina might have benefited from was access to the full continuum of services for children at imminent danger, and this continuum includes safe and secure treatment facilities that are therapeutic, culturally-informed, and effective – or, as Tina described to her CFS agency, a place where it feels like home,” Penrose’s report continues.

And lastly, Penrose points at Manitoba Families to create a new protocol with individually-tailored response plans for missing kids. “Access to time-sensitive safety and care information about children who are missing might mean the difference between life and death for some youth.”

The report says response plans specific to each case are imperative because of a strong correlation between missing persons, sexual exploitation, and “other harms that can place young people at immediate risk of injury and death.”

The highly anticipated report was released on Tina’s home reserve.

Not much has changed since Tina’s 2014 death: Penrose

Over the course of the investigation, Penrose said one thing had been made abundantly clear–that not enough has changed since Tina’s tragic death five years ago.

“In fact, what we know to be true from the youth we are working within our advocacy program and who are still alive today, and which has been confirmed by public systems throughout this process, is that children and youth who present with the same issues today may find themselves getting the same responses and experiencing the same barriers to service that Tina did.”

Penrose urges the government agencies to heed her recommendations as change cannot be put off any longer, since for many at-risk teens struggle with structural barriers for many months and years and the “downward spiral gathers speed rapidly”.

She said in her report that interventions and critical response measures often–and in the case of Tina–come too late because a threshold must be met before action is triggered.

“Our track record in Manitoba is not good. We are home to the highest numbers of children in care, highest numbers of youth in custody, and highest numbers of missing children. These are the outcomes when services and investments are not intensively targeted on the early years and on the prevention of crisis.”

Now, according to the advocate, Manitoba needs to jump to a more proactive approach.

“The solutions lie upstream. If the focus of our resources and interventions keep our eyes locked on the results of trauma, then we will ignore the reasons that cause the trauma and our province will continue to see ballooning numbers of youth involved in child and family services, youth justice, and youth who are in need of emergency detox and treatment.

“We can do better.”

-with files from the Canadian Press